Feature

Top 10 TV shows of 2015

TV Feature

Ed Williamson

3rd January 2016

I almost did it. Almost went my first Christmas period for five years without having to think about the end-of-year list. But then I thought of you, who is reading this now, and even though statistically you most likely are either my mother or the Googlebot spider, I decided I couldn't let you down. Also I'm on hold to TalkTalk and have nothing else to fill the time.

(A Fargo spoiler follows: skip a couple of paragraphs if you haven't seen it. Or if you're thinking "Shut up and make with the list already.")

A show that didn't quite make it in this year is Fargo, on whose second season I only just caught up. But there was a significant scene in its penultimate episode, where a shoot-out is interrupted by a flying saucer. Nothing other than realism had been suggested up to this point. Some characters were surprised; Kirsten Dunst's Peggy wasn't at all, and then everyone just got on with it.

It's hard to stress just how much of a creative no-no this would've been just a few years ago. Where once it would've been the ultimate lazy cop-out by a writer unable to get his characters from point A to point B, leaving viewers up in arms, I've seen no backlash against it. The rules have changed and we're happy to accept them.

Some on this list can trace back their influences to shows like The Sopranos and The Wire, and two suggest the welcome renewal of a dead genre, reinvigorated by public appetite for online speculation. By now we expect great TV rather than being pleasantly surprised by something better than average, and the medium is finally where it belongs: not a fall-back for anyone who couldn't get into the movies, but the best location for in-depth, long-form storytelling and rich character development. Not so much number 10, admittedly.

I don't have a lot of time for gentle TV. Nor much for Peter Kay anymore, come to that. But 2015 saw his return to acting in two well-behaved and yet great BBC shows: Danny Baker's Cradle to Grave, in which Kay plays the young Baker's cockney father, and Car Share.

The fact it's called Peter Kay's Car Share is an indication that his personal brand still sells (and also that he's partial to taking over a project, having come on board as an actor but ended up directing all the episodes and rewriting the scripts) but no matter. The twist on the standard odd-couple-stuck-together sitcom routine here is that the pair, both supermarket workers (Kay and Sian Gibson) having to car-pool to and from work, grow fond of each other rather than rancorous. Kay retains his natural ability to be funny simply by talking, the restricted environment giving him great licence to do so, and Gibson more than matches him. The obvious ending where they profess their love for each other never quite comes and it's all the better for it.

There are times when I think Dave is a quietly subversive channel, from its sign-off before the advert breaks ("Now here are some short films about capitalism") to the fact that its Twitter account is one of the canny new corporate breed that is funny and rarely bothers to advertise its products.

Al Murray's standing in character as The Pub Landlord against Nigel Farage in 2015's general election for the seat of South Thanet was one of the best pieces of political satire I've seen. For Dave, filmmaker Amanda Blue followed Murray on the campaign trail, creating a mockumentary in which he remained more or less in character throughout, an opportunity perfectly realised to ape politicians' habit of stressing that they are normal guys who like a pint and know who Taylor Swift is, and announcing nonsensical populist policies in line with where they think public opinion is ("Free dogs"). Donald Trump is currently in the process of taking this satire one step further.

Taking his charges into the age of New Order, Gazza and massive flares, Shane Meadows tied up his saga with emotional gut-punches harder than an Oakenfold beat dropping in a field full of pilled-up Mancunians.

Thomas Turgoose as Shaun did some terrific "on ecstasy" acting, nailing the excited jabber and gushing enthusiasm in a way usually misjudged, and Stephen Graham's ghost at the feast Combo finally had to atone for the beating he gave Milky in the film. Rather than just a nostalgia trip, This is England ended up an astonishingly deep working-class character study, with everyone bearing the scars in one way or another of poverty, abuse and drugs. But it should probably stop now, because a major arc is tied up, and because it's hard to know where they'd go from here into 1992, unless Woody ends the Cold War or something.

A late entry, so compelling I watched all ten episodes in about three days. Picking up on the renewed mainstream appetite for detailed true crime investigation after the Serial podcast, this Netflix documentary series is able to correct the main problem with Serial: the fact that an audio format trying to take on testimony from multiple witnesses, experts and investigators often leaves you confused as to who is who and where you are.

Making a Murderer plays powerfully on your sense of injustice, an emotion usually the reserve of the little-guy-versus-The-Man courtroom movie, with all the same dramatic beats. Its earlier episodes keep you guessing as to whether Steven Avery is guilty, before it takes a definite stance that he is not. The problematic thing is that a jury convicted him and Brendan Dassey, and yet everyone who watches this thinks them innocent, so you have to remember you're watching it through the anything-goes filter of how you usually perceive criminal cases on screen.

A TV audience can be completely convinced that a police force is corrupt but a jury will struggle to, because corrupt police forces exist quite readily in fiction and the idea is not alien to viewers. In real life it's hard – and frightening – to swallow. We watch this in the same way we watch fiction and, as many problems as that can cause, the boundaries are skilfully blurred here.

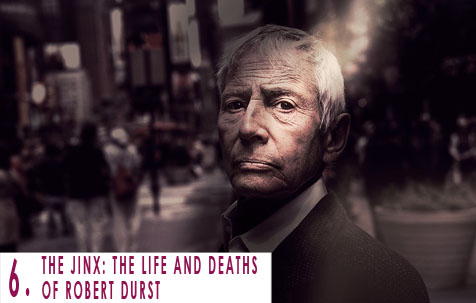

The earlier of this year's two true-crime bookends, The Jinx is a very different beast, less forensically detailed and featuring reconstructions, and more interested in getting inside a deeply strange man's mind.

Multimillionaire Robert Durst, suspected of two murders and acquitted of a third (despite admitting to having dismembered the corpse) agreed to participate in Andrew Jarecki's six-part documentary series. What was in it for him is known only to his disordered mind: he was free and clear, had nothing to gain and everything to lose. The result is astonishing in its dramatic tension and crammed full of detail you can barely believe, and culminates in Durst confessing while muttering to himself in the bathroom, not realising his microphone is still on. He was arrested the day before the finale aired.

Jarecki and his crew had effectively mounted their own investigation by making the series, and if Durst was motivated to cooperate by narcissism then it demonstrates how self-destructive an ambition the hollow desire to see oneself on TV really is. X Factor auditionees take note.

Follow us on Twitter @The_Shiznit for more fun features, film reviews and occasional commentary on what the best type of crisps are.

We are using Patreon to cover our hosting fees. So please consider chucking a few digital pennies our way by clicking on this link. Thanks!

Support Us

Follow Us

Recent Highlights

-

Review: Jackass Forever is a healing balm for our bee-stung ballsack world

Movie Review

-

Review: Black Widow adds shades of grey to the most interesting Avenger

Movie Review

-

Review: Fast & Furious 9 is a bloodless blockbuster Scalextric

Movie Review

-

Review: Wonder Woman 1984 is here to remind you about idiot nonsense cinema

Movie Review

-

Review: Borat Subsequent Moviefilm arrives on time, but is it too little, or too much?

Movie Review

Advertisement

And The Rest

-

Review: The Creator is high-end, low-tech sci-fi with middling ambitions

Movie Review

-

Review: The Devil All The Time explores the root of good ol' American evil

Movie Review

-

Review: I'm Thinking Of Ending Things is Kaufman at his most alienating

Movie Review

-

Review: The Babysitter: Killer Queen is a sequel that's stuck in the past

Movie Review

-

Review: The Peanut Butter Falcon is more than a silly nammm peanut butter

Movie Review

-

Face The Music: The Bill & Ted's Bogus Journey soundtrack is most outstanding

Movie Feature

-

Review: Tenet once again shows that Christopher Nolan is ahead of his time

Movie Review

-

Review: Project Power hits the right beats but offers nothing new

Movie Review

-

Marvel's Cine-CHAT-ic Universe: Captain America: Civil War (2016)

Movie Feature

-

Review: Host is a techno-horror that dials up the scares

Movie Review