Feature

Jurassic Park Week: Making pre-history: The story of Jurassic Park

Movie Feature

Ali

20th September 2011

As Jurassic Park prepares to roar back into cinemas this week, we look at how Steven Spielberg ushered cinema into the 21st century by revisiting the age of the dinosaurs...

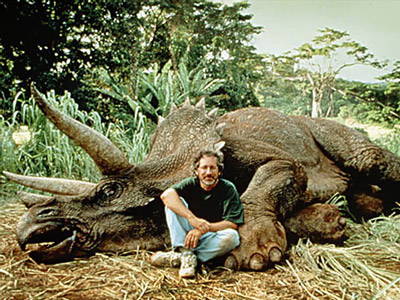

Spielberg's eyes widened. He wanted to hear more. A dinosaur lover from an early age, Spielberg had always been fascinated by Earth's mighty ancestors – with thoughts of Triceratops and Brachiosaurs stomping through his mind, suddenly doctors and nurses didn't seem so important. Eventually, after being pressed for more and more information over dinner, Crichton gave up the whole story. Spielberg sat in silence, cogs whirring. He had already begun storyboarding Jurassic Park in his head - and his food was stone cold.

A best-selling book and a box-office blockbuster, Jurassic Park remains one of the most spectacular stories of the recent age. On the surface, it appears to have much in common with its titular theme park – a rollercoaster ride full of thrills, spills and truly unforgettable experiences. At its heart though, Crichton's story taps into a deep-seated fear of man's fractured relationship with science, and the boundaries that lie therein. Fittingly, in order to bring Jurassic Park to life, Steven Spielberg would have to push a few boundaries himself. Cinema itself would evolve as a result.

Creating dinosaurs for the big screen had proved frightfully difficult in the past, and unless you were willing to use jerky stop-motion miniatures or dress a guy up in a rubber suit, your options were limited. Spielberg's initial plan to resurrect the residents of Jurassic Park was to work with Bob Gurr, who created the giant inflatable animatronic King Kong at Universal Studios, but the idea was dismissed as outlandish and just too damn expensive ("I initially wanted all the dinosaurs to be full-sized," said Spielberg, "but that was just my wishful thinking").

Eventually, Spielberg brought together four figureheads from the world of special effects: practical effects guru Stan Winston; stop-motion supremo Phil Tippett; ILM visual effects expert Dennis Muren; and special effects supervisor Michael Lantieri. His mission statement was simple: "I want people to say, 'Gee, this is the first time I've ever seen a dinosaur!'"

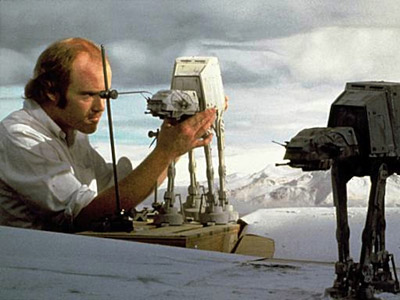

The reality was not so simple. While Stan Winston's impressive animatronics were just the ticket for close-ups – most memorably the infamous shot used in the trailer, in which the T-Rex eyes up two tasty morsels through the window of their Jeep – full-length shots of the dinos were proving more problematic. The idea was to use Tippett's pioneering Go-Motion technique – as used on AT-ATs and Tauntauns in The Empire Strikes Back – to animate the creatures, adding a 'motion blur' between each frame to eliminate the jerkiness. But it wasn't perfect. Far from it.

Animation tests were passable, but when the shots were composited with humans, they lacked the realism the story so desperately required to instil a sense of danger. It was about the time Spielberg started pulling the brim of his cap low over his furrowed brow that Dennis Muren piped up: "Would you ever consider letting us do the full-sized dinosaurs from head to toe on the computer?" Prove it, said the director. And prove it he did.

Nowadays, the idea of a realistic, fully computer-generated character isn't that much of a stretch, but back in the early nineties – when CG was still in its infancy and computers had roughly the same processing power as your average iPhone app – it was still considered a risk. Save for the water tendril in The Abyss and the T-1000 in Terminator 2, ILM had never animated a living creature. Not yet a CG convert, Spielberg had images of "Nintendo style dinosaurs" cheapening his movie, but Muren and his team showed the director exactly how far digital animation had come – and what massive potential it had.

"There we were, watching the future unfolding on the TV screen, so authentic I couldn't believe my eyes," remembers Spielberg. "I turned to Phil [Tippett], and he said to me: 'I think I'm extinct.'" Keen to retain his expertise on dinosaur movement and behaviour, Spielberg combined Tippett's team with Muren's ILM squad and decided to forge ahead with CGsauruses. Later, Tippett would hear palaeontologist Alan Grant utter almost his exact same exasperated phrase in the movie.

With his pixelated prehistoric performers roaming the render farm while they waited for their screen debut, Spielberg set about rounding up Jurassic Park's human element. Sam Neill was to play protagonist and skeptic Alan Grant, after William Hurt turned the role down, while Laura Dern signed on to play fellow dino-digger Ellie Sattler, beating out Juliette Binoche and Robin Wright. Richard Attenborough would bring gravitas to the role of billionaire park owner John Hammond, favoured over Sean Connery, while Jeff Goldblum brought the funny as chaos theorist Ian Malcolm.

Interestingly, Hammond and Malcolm came to represent not only opposite ends of the moral barometer (one always dressed in white, one clad in black), but also Steven Spielberg and Michael Crichton respectively – one man the fantastist and dreamweaver, the other the realist and the nagging voice of reason. It was an irresistible clash of ideals on every level. "I didn't cast movie icons or stars," said Spielberg. "I tried to cast really, really good actors."

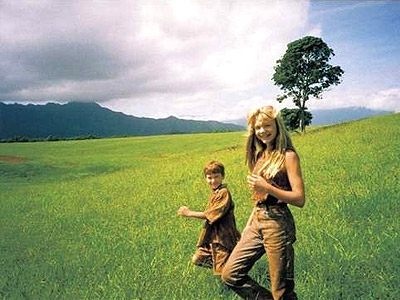

Three weeks of shooting on the Hawaiian island of Kaua'i commenced in August 1992. The decision to digitally add in CG dinosaurs in post-production actually gave the practical effects teams more work to do – every element of the scene that a computer-generated character touched (or, more accurately, stamped on/headbutted/destroyed) had to react in a way that computers couldn't always render realistically.

Filming in such a tropical environment did cause a few headaches for Spielberg and his crew, not least when the final days of shooting were rudely interrupted by Hurricane Iniki ("It was like a bad movie," recalls the director. "I turned on CNN and instantly there was a map of Hawaii on the TV, with an icon for a hurricane pointing directly at our island"). Weather led to further issues, particularly when artificial rain played havoc with Stan Winston's incredibly complex – and unfathomably expensive – T-Rex robotics, which would absorb water and judder horrifically. Crew members would blast the Rex's head with hairdryers before a scene, but rain stopped play more than once – even history's deadliest predator gets the sniffles occasionally.

Support Us

Follow Us

Recent Highlights

-

Review: Jackass Forever is a healing balm for our bee-stung ballsack world

Movie Review

-

Review: Black Widow adds shades of grey to the most interesting Avenger

Movie Review

-

Review: Fast & Furious 9 is a bloodless blockbuster Scalextric

Movie Review

-

Review: Wonder Woman 1984 is here to remind you about idiot nonsense cinema

Movie Review

-

Review: Borat Subsequent Moviefilm arrives on time, but is it too little, or too much?

Movie Review

Advertisement

And The Rest

-

Review: The Creator is high-end, low-tech sci-fi with middling ambitions

Movie Review

-

Review: The Devil All The Time explores the root of good ol' American evil

Movie Review

-

Review: I'm Thinking Of Ending Things is Kaufman at his most alienating

Movie Review

-

Review: The Babysitter: Killer Queen is a sequel that's stuck in the past

Movie Review

-

Review: The Peanut Butter Falcon is more than a silly nammm peanut butter

Movie Review

-

Face The Music: The Bill & Ted's Bogus Journey soundtrack is most outstanding

Movie Feature

-

Review: Tenet once again shows that Christopher Nolan is ahead of his time

Movie Review

-

Review: Project Power hits the right beats but offers nothing new

Movie Review

-

Marvel's Cine-CHAT-ic Universe: Captain America: Civil War (2016)

Movie Feature

-

Review: Host is a techno-horror that dials up the scares

Movie Review