Review

Detachment

Movie Review

| Director | Tony Kaye | |

| Starring | Adrien Brody, Sami Gayle, Christina Hendricks, Marcia Gay Harden, James Caan, Lucy Liu, Bryan Cranston | |

| Release | 13 JUL (UK) Certificate 15 |

Ed Williamson

11th July 2012

'Elegiac': one of those words of whose meaning you've never quite been certain, but you're fairly sure you'd know the thing it describes when you saw it. Now, I reckon Detachment is pretty elegiac. It certainly felt like it. The word kept popping into my head the whole time I was watching it. So bear with me for 900 words or so while I try to figure out whether it was, then I'll look it up. Oh, and if the promise of a dictionary definition's not enough for you, this is one of the best films I've seen all year. Just saying.

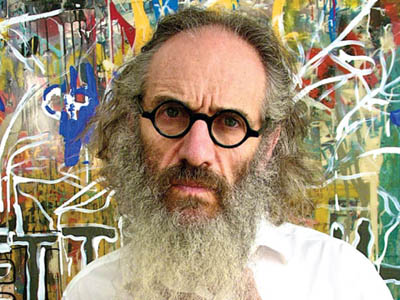

This is the work of British director Tony Kaye, whose last meaningful Hollywood exchange was with 1998's American History X, during which he reportedly proved impossible to work with, arguing constantly on set with Edward Norton – himself no slouch in the awkward bastard stakes – and tried to have his name taken off the directorial credits and replaced with 'Humpty Dumpty'. He still considers the finished result short of what he was attempting. He seems happier with Detachment, though Bryan Cranston's report from the set was that "Tony Kaye is a very complicated ... interesting fellow".

Uh ... yeah, he looks it.

Right, key themes, key themes ... oh, oh! Detachment! That's a theme in itself! And it's right there in the title. What a giveaway. Adrien Brody is Henry Barthes, a supply teacher (wait, they never stay in one job more than a few months, so they're ... detached! Yes, detached!) at a school everyone's stopped caring about. The pupils are just marking time, the parents don't care unless they can get a free laptop by saying their child has ADHD, and principal Marcia Gay Harden's on her last legs before the District turfs her out. He has a grandfather stricken by Alzheimer's in a nearby nursing home, and before long he's also taken in a teenage prostitute as a lodger.

His reasons for doing this are obscure: as innocent as the relationship genuinely is, it would mean the end of his career if discovered. Perhaps he just wants to do some good in a child's life when he spends his working days resignedly failing to, but if so he does it without appearing to emote with her. "Have you recently been raped?" he asks, seeing some trauma on her inner thigh. "What do you care?" she shoots back. "I'm not sure that I do, particularly," he replies. "But I can put something on it for you." If I knew what the adjectival form of 'Camus' was, I'd probably use it here.

He forms an understanding of sorts with fellow teacher Christina Hendricks, and lights a spark of inspiration in Meredith (director's daughter Betty Kaye), an outsider pupil whose Parents Just Don't Understand. She, along with more or less every character here, is detached in their own way, as exemplified in a key scene halfway through, where the focus shifts from Brody to show everyone else in their home life one evening. It goes without saying none of them is a lot of fun: we can infer every soul-destroying year of Harden's marriage to Bryan Cranston in the space of the two minutes we see them together.

Jeeze, get a room. No, wait! DON'T!

Kaye shoots all of this almost like a documentary at times, with frequent close-ups and hand-held cameras, sometimes deliberately alienating us by ham-fistedly adjusting the lens halfway through a scene. A raft of stylised tics assault us throughout: a sudden POV shot or camera zoom down a corridor; childhood flashbacks shot in Super 8 style; cuts to Brody's unexplained interview-style voiceover; the frequent use of stop-motion animated drawings on a blackboard to mirror a character's thoughts when they're spinning out of control. It makes us feel ... oh, right: detached.

Brody's performance is strong enough to anchor us and guide us through it all, without his ever being an especially sympathetic central character. He doesn't even seem all that inspirational a teacher: any hint that we might stray into mawkish Dead Poets Society territory is quickly dashed. Sixteen-year-old Sami Gayle props him up with a performance of haunting vulnerability as the teenage prostitute.

And I loved it. All of it. But it stumped me as to why. Certainly it reminded me of Half Nelson, a film I'd happily eat for breakfast every morning, but there's more: like TV's The Wire, Detachment documents the failure of an institution, and lets us see the fallout on the people within it. But moreover, it wants us to know that the people within it aren't failures if they still care about it. In doing so, it lets us see inside the soul of a man who desperately wants to do good in the world, but can't overcome his own detachment from it. Which is pretty elegiac if you ask me.

That means "of, relating to, or involving sorrow, especially for that which is irrecoverably past", as it turns out. To be honest, I thought it was something to do with elephants.

Follow us on Twitter @The_Shiznit for more fun features, film reviews and occasional commentary on what the best type of crisps are.

We are using Patreon to cover our hosting fees. So please consider chucking a few digital pennies our way by clicking on this link. Thanks!

Support Us

Follow Us

Recent Highlights

-

Review: Jackass Forever is a healing balm for our bee-stung ballsack world

Movie Review

-

Review: Black Widow adds shades of grey to the most interesting Avenger

Movie Review

-

Review: Fast & Furious 9 is a bloodless blockbuster Scalextric

Movie Review

-

Review: Wonder Woman 1984 is here to remind you about idiot nonsense cinema

Movie Review

-

Review: Borat Subsequent Moviefilm arrives on time, but is it too little, or too much?

Movie Review

Advertisement

And The Rest

-

Review: The Creator is high-end, low-tech sci-fi with middling ambitions

Movie Review

-

Review: The Devil All The Time explores the root of good ol' American evil

Movie Review

-

Review: I'm Thinking Of Ending Things is Kaufman at his most alienating

Movie Review

-

Review: The Babysitter: Killer Queen is a sequel that's stuck in the past

Movie Review

-

Review: The Peanut Butter Falcon is more than a silly nammm peanut butter

Movie Review

-

Face The Music: The Bill & Ted's Bogus Journey soundtrack is most outstanding

Movie Feature

-

Review: Tenet once again shows that Christopher Nolan is ahead of his time

Movie Review

-

Review: Project Power hits the right beats but offers nothing new

Movie Review

-

Marvel's Cine-CHAT-ic Universe: Captain America: Civil War (2016)

Movie Feature

-

Review: Host is a techno-horror that dials up the scares

Movie Review